Cambridge, England —(Map)

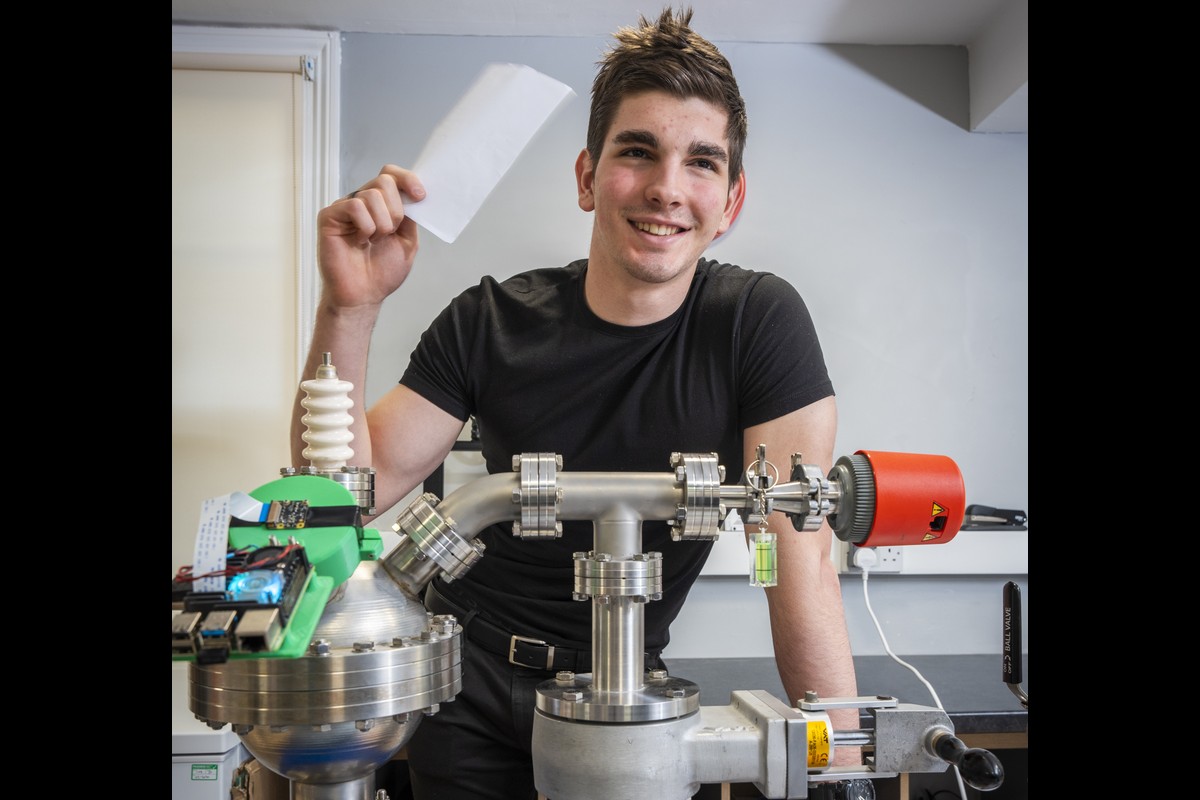

Cesare Mencarini recently graduated from a sixth form school (high school) in England with excellent grades. But he was probably more excited about the success he had the previous year – building a working nuclear fusion reactor at the age of 16.

Fusion

Fusion energy is created when hydrogen atoms “fuse” together (join). This reaction is what gives the Sun and other stars their incredible energy. Many people see fusion energy as the perfect energy for the future. The fuel needed for fusion reactions is cheap, and there’s plenty of it. And if scientists can figure out how to make it work, fusion could easily provide all the energy the world needs with very little pollution. But the goal of creating usable fusion power is still a long way off.

Cesare grew up in Italy, but he’s been going to school at Cardiff Sixth Form College in Cambridge, England for the last two years. His focus was on math, chemistry and physics.

(Source: Cesare Mencarini.)

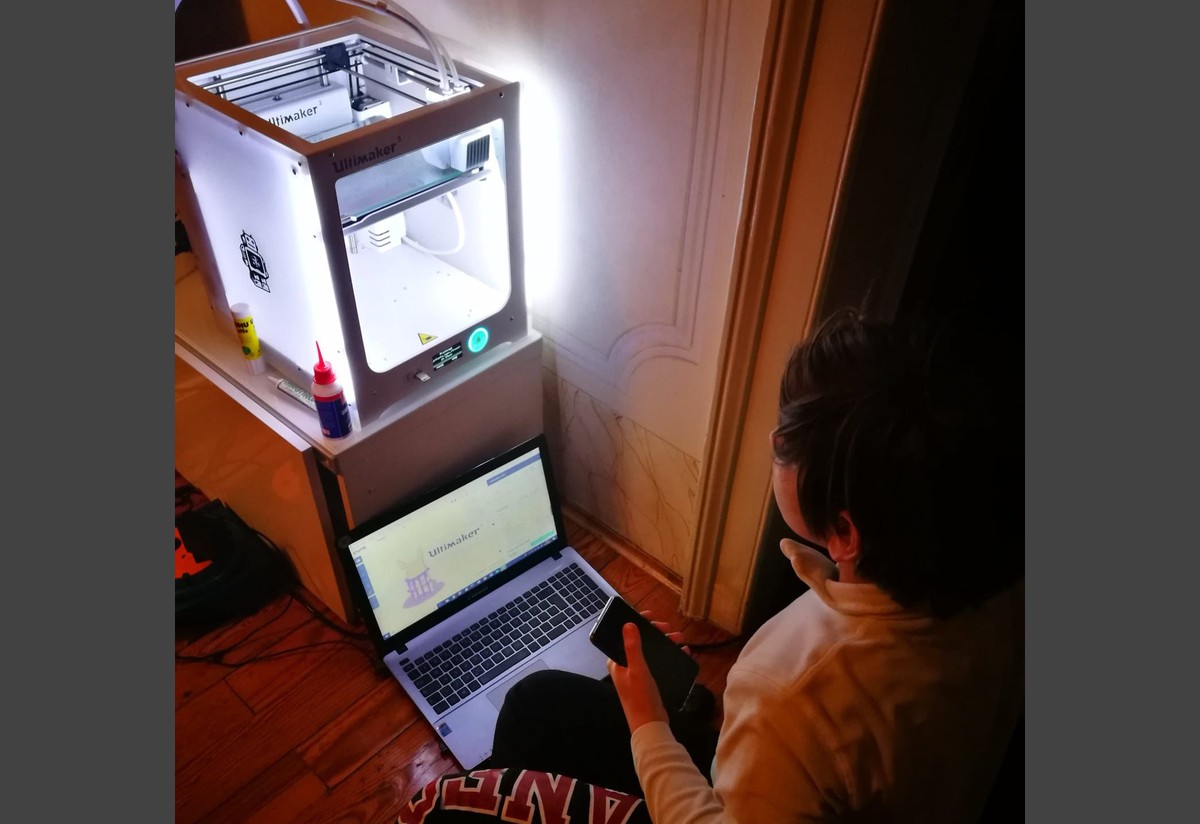

Cesare’s mother is an architect and his father is an electronic engineer. As a child, Cesare became interested in electronics. He loved to experiment. He learned to program computers and devices like the Arduino and Raspberry Pi. He also worked with a 3D printer.

At Cardiff, Cesare was allowed to choose an extra area of study. After seeing a video about someone building a fusion reactor, Cesare decided he wanted to build one, too.

The school wasn’t so excited about the idea. But Cesare worked to persuade his teachers. Finally, after a complete safety review, and with an extra advisor offering to help out, the school agreed.

(Source: Cesare Mencarini.)

Cesare was a strong student, but his regular classes weren’t teaching him how to build a fusion reactor. To learn this, he spent countless hours doing research, looking up information on the internet, and watching videos.

“We’re living in an age where everything is available just by searching,” he says. When he faced a problem, he would read, watch 10 or 15 videos, and then go try to tackle the problem. He also joined a website where he got advice from scientists with more experience.

Step by step, working long hours with his physics teacher and his advisor, Cesare built the reactor. Last June, at the very end of the school year, the reactor was finished.

(Source: Copyright Neil Phillips, Dukes Education.)

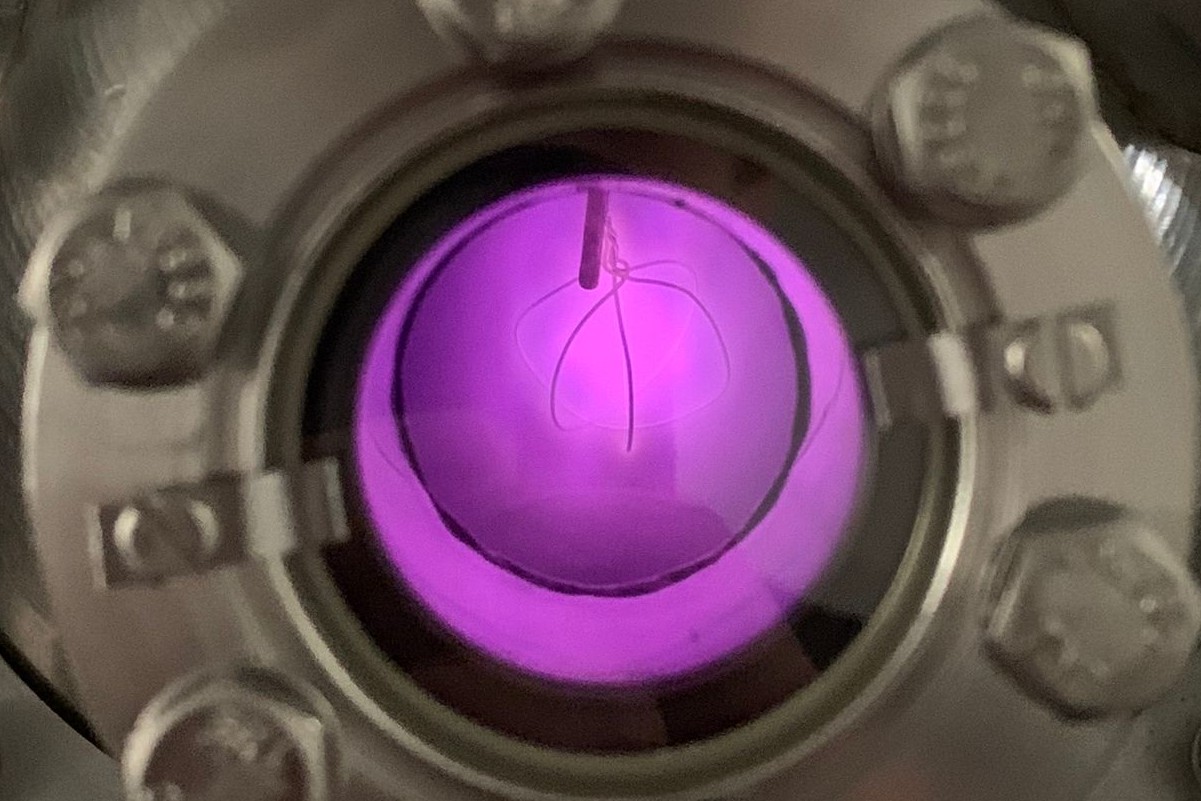

One important step in building a fusion reactor is to “achieve plasma”. That’s when atoms are so excited (heated up) that they gain or lose electrons, creating a glowing gas* called plasma.

But Cesare still couldn’t get the reactor to achieve plasma. A special piece of metal that was supposed to fit perfectly in the device didn’t fit well. The seal kept leaking.

Finally, Cesare and the others decided to try filing down the piece of metal by hand. That failed four times. The team was almost ready to give up. But the next time, the seal held and the reactor worked, creating plasma. Cesare could barely believe his eyes. “It works!” he cried, excitedly.

(Source: Cesare Mencarini.)

Over a year has passed since then. Cesare has continued to improve the reactor. He’s built complicated devices to control the pressure and to better see and understand what’s going on inside the reactor.

He’s one of the youngest students to have built such an advanced fusion reactor. But for Cesare, it wasn’t just about the reactor. It was also about learning by doing, and about making connections with other people doing similar things.

College is the next stop for Cesare – perhaps in England, perhaps in Italy. No matter where he goes, he’ll probably continue to change people’s ideas about how much young people can achieve.

Did You Know…?

One problem Cesare faced was money. The school approved his project, but they only gave him 25% of the money he needed. Cesare says not having much money meant he had to be very creative, and as a result, he wound up learning much more.

* Plasma is not actually a gas, but a special “ionized state” of matter. Scientists recognize four states of matter: solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. In everyday life, we commonly come across the first three. Lightning and neon lights are examples of plasma.

😕

This map has not been loaded because of your cookie choices. To view the content, you can accept 'Non-necessary' cookies.